by Norman L. Kincaide, Ph.D.

The perceived prestige of historic designation for inclusion in the National Register for Historic Places may not be worth the effort, for once a property is so designated it falls under the National Historic Preservation Act and specifically Section 106. This means that a private land owner’s property falls under federal scrutiny for failure to comply with said act. This situation has engendered considerable opportunity for abuse by the National Park Service and those who promote historic preservation. This abuse erodes the rights of private property owners whose property may have been designated or whose property falls within a National Historic District or a National Heritage Area.

Those who are charged with advising local government entities on issues of historic preservation may have agendas that affected property owners may not be aware. Land owners find out when confronted with the restrictions imposed based upon unelected boards advising or pressuring, local elected boards to do their bidding. The mantra and trip wire for enforcement of Section 106 is: If one dollar of federal money is spent on a project then Section 106 compliance comes into play. This is not a casual statement, but rather is used as the means to control how private property owners use their land from renovation, to construction, to how their view shed is evaluated and classified.

In this respect Section 106 is used as a litigation engine to drive compliance with the National Historic Preservation Act. Land owners need to know how this may affect the use of and future plans for their property. Historic designation is part of a plan that has already targeted the private property in question, which the owner is entirely unaware, until he wants to make changes to his historically designated property. The land owner may become involved in prolonged and costly litigation against a myriad number of governmental and not for profit entities who may have an interest in how the property owner uses his land.

This, seemingly, innocent designation may also involve the land owner in the internecine struggle between the Army Corps of Engineers and the National Park Service. The National Park Service has long had issues with the Army Corps of Engineers noncompliance with Section 106 in its permitting process. The land owner must be aware that if his land is even adjacent to a property that has been historically designated that he or she may become involved in such an internecine dispute between the Army Corps of Engineers and the National Park Service.

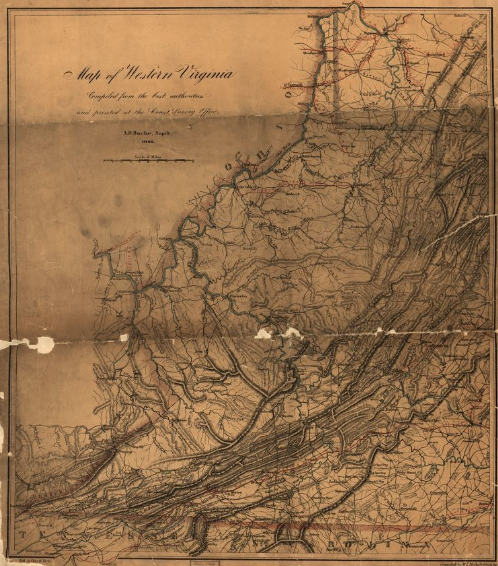

A case involving National Park Service abuse of power is United States v. Blackman, filed June 2004 in the US District Court for the Western District of Virginia. This civil action pertained to the validity of a historic preservation easement and whether such a negative easement in gross was cognizable under common law in the state of Virginia and whether this easement could be lawfully conveyed and accepted by the National Park Service and whether NPS claims of enforcement authority were barred by estoppel, waiver, acquiescence, abandonment or by breach of the easement’s terms. In addition to the civil action the National Park Service also filed a criminal complaint against Blackman on the theory that he broke an injunction against the renovation of his home. The NPS interpreted Blackmon’s performance of necessary repairs to his home as “renovations.” The stacking of the criminal complaint upon the civil action appears to comport with a long-running and well-documented pattern of vindictive retaliation against property owners who do not conform to the exact dictates of National Park Service bureaucracy or who are not favored by the local preservationist community.

This easement was conveyed by one of Blackmon’s predecessors in ownership to Historic Green Springs Incorporated, a non-profit Virginia corporation. The purpose of the easement was to preserve what historic preservationists called a “historic farm” and its “manor home” lying within the 14,000 acre Green Springs Historic District. Historic Green Springs assigned Mr. Blackman’s easement, along with many other easements in the District, covering about 7000 acres to the United States. The National Park Service claimed authority to administer and enforce the terms of the purported easements that it held in the historic district.

When Peter Blackman purchased the farm in 2002, he faced a daunting task of repair and restoration work on a home suffering from long neglect, weather and storm damage, structural deterioration, and toxic mold growth on interior walls. Electrical wiring, plumbing and heating systems were inadequate and unsafe. Not only did Blackman plan to architecturally restore the home to reflect its former beauty and character, inside and out, he also desired a comfortable home with modern conveniences.

Blackman was not alone in these circumstances of abuse. A neighbor of Blackman’s, Jo Anne Krahenbill, wrote a letter to the Subcommittee on National Parks in which she wrote: “As an owner of a property covered by the National Register, I can confirm that such a listing can be a nightmare. My father, a real farmer, was an organizer of the district and initially supported the notion of conservation easements . . . He came to rue the day he contributed an easement on his property. Throughout the ownership of the farm, he was hassled and harassed by the Park Service. They told him he could not make any changes on his house, even on the interior, as the condition of the house deteriorated . . . the current owners have been able to do the very things my father was forbidden from even considering. These current owners are tight with Historic Green Springs Incorporated, an organization the Park Service seems to always do the bidding of, regardless of right or wrong.”

Earl W. Poore, a builder, stated in another letter to the Subcommittee, “I was involved in the creation of the historic district and the conservation easements. My experience with the National Park Service has been radically different from what they promised us beforehand . . . it has been a constant battle, for me and others, except those who are part of an organization, [HGSI] to whom the Park Service seems to be in cahoots with. This organization is run by a woman who got control . . . has since tried to control everything that goes on here like her personal fiefdom.”

Another resident, D.L. Atkins explained: “I contributed well over 1,500 acres [into easements] and did not receive any tax credits. . . I did not get a single penny for all the substantial property rights I gave up. In return I had been treated with suspicion and like an adversary . . . the Park Service led us to believe that our easements would be treated like scenic easements and they would allow us to manage our properties just like we had been doing before. . . Once the Park Service had actual control of the easements, they changed their tune. . . If I could do things over, I would never have donated a single conservation easement that could end up under the management of the Park Service.”

There have been historic designations which have been withdrawn by local governments. On December 19, 2002 the Monterey Town Council of Monterey, Highland County, Virginia, voted 4 to 2 to abolish the town’s historic district. The Monterey Historic District had been in place since 1981, encompassing the whole town, one of 200 local districts throughout Virginia. Monterey, established in 1848, lies in western Virginia, the county seat of a sparsely populated Allegheny Mountain community with a total population of about 2600 with an economy based on cattle, sheep and timbering.

For 20 years town residents and property owners chaffed under an unneeded layer of government. A majority of residents were fed up with what they called arbitrary decisions, ego clashes, arrogance, and bureaucratic restrictions on economic development, home improvements, and property rights by the Architectural Review Board which applied Historic District Guidelines for new construction, renovation and demolition. The guidelines were in fact not guidelines, but enforceable local regulations patterned on federal and state standards, the formulation and publication of which were partially funded through the National Park Service.

In addition to the historic district Monterey was designated as one of twenty-eight Department of Historic Resources Certified Local Governments (CLG). The CLG program was created by the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended in 1980, established a partnership between local governments, the federal preservation program, and the Department of Historic Resources providing a means for local governments to participate more formally in state and national historic preservation programs. The programs include an array of tax credits, grants, and educational efforts, many of which promote and implement federal, state and local controls of private property under the banner of historic preservation (conservation) easements, preservation planning, and economic/tourism development and promotion.

Due to the action of the Monterey Town Council the CLG status was placed in jeopardy because one of the benchmarks for certification under the federal certified government is that the local government entity has a historic preservation ordinance. The decision was made after a nine month long county-wide debate and dire predictions by pro-historic district adherents that Monterey would suffer if it broke the covenant which brought federal grants, subsidies, tax rebates and technical assistance. The residents spoke by supporting and voting in town council members who also believed in abolishing the historic district designation. They believed that Monterey and Highland County would not only survive but prosper to an even greater degree without government historic district bureaucracy and the hindrance of CLG designation to sap individual initiative and community pride.

This is part of a far larger design by the National Park Service if you live in a National Heritage Area, National Historic District, or other federal protected area, to sideline the notion of a willing seller and replace it with condemnation, i.e. the power of eminent domain. This was clearly stated by the National Park Service in testimony for expanding the Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area stating: “the bill limits [NPS] land acquisition authority to willing sellers. We believe that this provision unfairly ties the hands of the [NPS]. Throughout the National Park System, we usually have the power of eminent domain . . . in case of severe and irreparable damage to the resource or to clear title, condemnation may be the only viable option . . . we believe the National Park Service, in alliance with its partners, would need to take a fresh look at the management of entire national recreation area.”

So when the willing seller option does not work, the federal government desires to employ condemnation to expand land acquisition and management. In 1972 the Buffalo National River in the Ozarks was created with the caveat that forcing land owners off the land was expressly prohibited. The people, their homes and culture were supposed to be preserved. At that time there were 1,108 private land owners along the river. By November 2005 there were only eight private land owners left.

Private property owners must also understand the implications when legal challenges are filed against them to enforce Section 106 compliance. The clear intent of Congress in enacting the National Historic Preservation Act was that “any interested person” be entitled to bring an action in federal court to enforce the provisions of the Act” and to recover attorney’s fees if he or she substantially prevails in that action. This means that private property owners may be faced with the prospect of litigation against some very deep pocket entities in partnership with the National Park Service, who can afford attorneys to bring their case to court along with the power of the federal government. This circumstance places the individual private property owner at a substantial disadvantage in any court battle with preservationist forces in alliance with the National Park Service.

In light of recent revelations about IRS, NSA, and Department of Justice abuses of power why would anyone want to have their property designated for the National Historic Register and deal with preservation issues and attendant compliance with Section 106? This also raises the question of whether entities of the federal government really act in the interests of the people or whether they are only interested in their own growth and self-aggrandizement at the expense of the taxpayers and private land owners. The United States Army, the National Park Service, and the Army Corps of Engineers appear to be competitive cancers feeding off of the same host, the competition for which made all the more strident in light of the implementation of sequestration. If a private property owner does not believe that their own property has not been already targeted by the National Park Service through a historic resources survey, perhaps they should ask those who belong to the Tea Party if they have been targeted by the IRS.

Sources:

The Virginia Land Rights Coalition, May 10, 2005, L.M. Schwartz, Historic Preservation Easement Challenged in US and Virginia Courts.

The Virginia Land Rights Coalition, January 13, 2003, L.M. Schwartz, Local Historic District Abolished.

The Virginia Land Rights Coalition, November 12, 2005, L.M. Schwartz, The Federal Contract on Your Land.

Charles M. Niquette, Section 106 Compliance on Trial: Russ and Lee Pye v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

National Trust for Historic Preservation v. United States Army Corps of Engineers, 552 F. Supp. 784 (S.D. Ohio 1982)